California fuchsia is one of those plants that feels like a cheat code. When everything else is fading in late summer, it lights up with electric red-orange flowers and pulls hummingbirds out of thin air. Native to California and parts of the West, this plant is built for heat, drought, and poor soils, and it gets better when you leave it alone. Scroll on for how to plant it once and enjoy it for years.

Is California fuchsia a good choice for my yard?

Yes, if…

- You want a late-summer bloomer that feeds hummingbirds

- You garden with well-drained soil

- You want a plant you don’t have to water once it’s established

- You like plants that spread gently and fill space over time

California fuchsia‘s light needs differ depending on where you live.

- If you live near the coast or in the northern part of its range, full sun is great.

- For more inland, hotter areas, part-sun works better. If it’s in full sun, give it extra water during hot summer days.

Why California fuchsia matters

- Late-season lifeline: Flowers when many native plants are done for the year

- Hummingbird favorite: Tubular flowers are perfectly shaped for long bills

- Drought-tough: Thrives on rainfall alone once established

- Low effort: No fertilizer, no fuss, no weekly care schedule (prune to the ground after they’ve bloomed and that’s it)

One plant, hundreds of flowers

These plants are maximalists when it comes to flowers. The USDA sums up California fuchsia’s commitment to flowering nicely (our bolding): “The plant often has over 250 blooms per flower blooming at one time.”

New to native?

Before lawns and landscaping, native plants were here. They’ve fed birds, bees, and butterflies for thousands of years—and they’ll do the same in your yard. The best part? They’re easier to grow than you think.

Where California fuchsia grows naturally

In the wild, California fuchsia grows in dry, sunny places across California and into parts of Oregon, Nevada, and Arizona. You’ll find it on rocky slopes, open hillsides, coastal bluffs, and canyon edges. All these places share excellent drainage and long, dry summers.

In a yard, that translates to sunny, well-drained spots where other plants might struggle. Slopes, borders, hellstrips, and gravelly areas are all fair game.

A quick note about the name (because it’s confusing)

Despite the name, California fuchsia is not a true fuchsia (it would need to be in the Fuchsia genus to be an official fuchsia). The flowers just look similarish. Botanically, it belongs to the evening primrose family (Onagraceae). The “fuchsia” common name comes from its looks, not lineage.

California fuchsia and hummingbirds: a multi-millennia partnership

California fuchsia isn’t just “popular with hummingbirds.” It’s a textbook example of hummingbird pollination, backed by decades of field research.

California fuchsias are bird-pollinated

When we think of pollinators, we often think of bees. But California fuchsia’s bright red, tubular flowers are shaped to match a hummingbird’s bill, not a bee’s body. Nectar sits deep inside the flower, accessible to hovering birds but difficult for most insects to reach. As hummingbirds feed, pollen brushes onto their foreheads and bills, then gets carried directly to the next flower. Pollination biologists classify California fuchsia as ornithophilous, meaning bird-pollinated.

See California fuchsia blooming? Watch out for hummingbird migrations

Timing matters too. California fuchsia blooms from late summer into fall, a period when many other nectar sources have faded. Research on hummingbird foraging shows that late-season flowers play an outsized role in supporting resident and migrating hummingbirds, especially in dry regions where resources drop sharply by August.

In other words: California fuchsia isn’t just hummingbird-friendly. It’s hummingbird co-evolved, offering the right color, shape, nectar access, and timing to keep both plant and pollinator thriving.

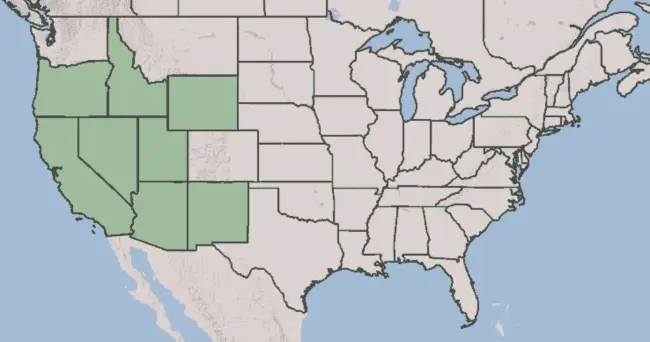

Where is California fuchsia native?

California fuchsia (also sometimes called ‘hummingbird trumpet’) is native from Wyoming to California.

How to grow California fuchsia

This plant likes:

- Sun: Full sun is best for compact growth and heavy flowering

- Soil: Well-drained soil is key; rocky or sandy soils are ideal

- Water: Water during the first growing season only; then it should be fine on its own*

- Pruning: According to CalSCAPE, “Best to cut it back to the ground as soon as the flowers are spent, and it will come back lush and healthy in the spring.”

- Spacing: Give it room to spread—many forms slowly creep and fill in

If California fuchsia flops, sulks, or doesn’t flower much, it’s usually getting too much water or too much shade. Avoid planting it in irrigated lawns or heavily watered beds.

*A watering note for inland gardens: this plant may need some water during the height of summer, especially if planted in full sun.

Growing San Diego has a helpful video that shows what to look for and how to plant California fuschias:

Where California fuchsia shines in your yard

California fuchsia is perfect for well-drained sunny areas. Use it along sunny edges, on slopes, or anywhere you want a low, spreading plant that looks intentional without constant care. The USDA sums it up nicely:, “The plants are extremely drought tolerant and withstand sun, heat, and wind, making them ideal plants for dry sunny slopes.”

California fuchsia is especially powerful when planted where you can watch hummingbirds hover and feed up close: near patios, windows, or walkways.

California fuchsia cultivars

There are many California fuchsia varieties and cultivars available. (A cultivar is a plant curated, selected, or bred by humans for characteristics like color, height, etc. Here’s a quick cultivar overview.) Some California fuchsia cultivars you may encounter include:

- California fuchsia ‘Catalina’: 3′ tall with larger red flowers and silvery leaves

- California fuchsia ‘Bert’s Bluff’: 3′ tall with a more compacted shape

- California fuchsia ‘Everett’s Choice’: A tiny border-friendly option; only 1′ tall

- California fuchsia ‘Pink’ or ‘Solidarity Pink’: light pink colored blooms instead of the fire engine red

Cultivars are complicated, hot topics within the botanical and native plant communities. A cultivar like ‘Solidarity Pink’ is a good example of why cultivars are worthy of discussion.

Hummingbirds have evolved to have heightened sensitivity to seeing red and yellow. When we plant a cultivar that has pink flowers, we may be inadvertently making it harder for migrating hummingbirds to find the California fuchsia blossoms and the nectar within. Some botanists and ecologists also argue that it’s best to leave nature and evolution alone and stick to planting “straight species,” or native species untouched or curated by humans.

What to do? Well, The Plant Native’s POV (if you care! totally fine if you don’t!) is to strive to plant straight species native to your area. That said, let’s not make our gardening choices feel like botany exams. Native cultivars (sometimes called nativars) are always better choices than lawn or non-native plants.

Hot outside? This plant might take a nap.

California fuchsia often goes dormant in summer drought, especially in hotter inland areas. Leaves may yellow or drop entirely. This isn’t stress—it’s strategy.

The plant conserves energy underground, then comes roaring back with flowers when conditions line up (and hummingbirds need the nectar). If it looks messy in midsummer, don’t panic. It’s just pacing itself.

Where can I get California fuchsia?

California fuchsia is widely available at native plant nurseries in the western U.S. Look for straight species or locally sourced forms adapted to your region. Here are some ideas on where you can find your own:

Where can I find seeds and plants?

Finding native plants can be challenging (we partly blame Marie Antoinette.) To make it easier, we’ve assembled four sourcing ideas.

300+ native nurseries make finding one a breeze

Explore 100+ native-friendly eCommerce sites

Every state and province has a native plant society; find yours

Online Communities

Local Facebook groups are a great plant source

What are good pairings for California fuchsia?

Pair California fuchsia with other sun-loving, low-water natives that won’t crowd it or demand extra irrigation. Native bunchgrasses, goldenrods, buckwheats, and sages/salvias make great companions. The goal is a planting that offers something for pollinators throughout the season and thrives in similar, well-drained, sunny spots.

Pairs well with

California fuchsia proves that low effort doesn’t mean low impact. Plant it in sun, give it a year to settle in, and then step back. When late summer hits and hummingbirds show up on schedule, you’ll understand why this native earns its reputation year after year. The only care you’ll need is to cut it back after it flowers, and it will be back next year to start the show again. Where to next? Can we recommend our Beginner’s Guide to Native Salvias or our Beginner’s Guide to Native Manzanitas? Happy planting!

Sources

- Snow, A. A. (1986). POLLINATION DYNAMICS IN EPILOBIUM CANUM (ONAGRACEAE): CONSEQUENCES FOR GAMETOPHYTIC SELECTION. American Journal of Botany, 73(1), 139-151.

- Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. “Epilobium canum (California Fuchsia).” Native Plant Information Network.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Epilobium canum.” USDA PLANTS Database.

- Jepson Flora Project. “Epilobium canum.” Jepson eFlora, University of California, Berkeley.

- University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. “California Fuchsia (Epilobium canum).” UC Master Gardener Program.

What if your feed was actually good for your mental health?

Give your algorithm a breath of fresh air and follow us.