Black-eyed Susans are resilient native flowers that bloom from late summer into fall. They thrive in full sun, part sun, and drought. After they flower, their seedheads feed birds through fall and early winter. Whether short-lived perennials or self-seeding biennials, they return year after year. Put the unfortunate common name aside (seriously—why does Susan have black eyes? Is she OK?!) and celebrate these plants for what they are: bright, tough, long-blooming natives.

Black-eyed Susans are super easy to grow

Is black-eyed Susan a good choice for my yard?

Yes, if…

- You want bright, summer-long color with almost no effort.

- You have full sun or part sun; these plants love heat.

- You want a native flower that thrives in dry or average soil.

- You’re building a pollinator garden or want a bird-friendly yard.

- You like plants that return on their own, either as short-lived perennials or by reseeding.

Why black-eyed Susans matter

- Late-summer workhorse: Blooms for 4–6 weeks when many gardens fade.

- Bird support: Seedheads feed goldfinches and other small birds.

- Pollinator magnet: Bees, butterflies, and native insects rely on their mid-season nectar.

- Time-saver: Drought-tolerant, low-maintenance, and happy with rain alone.

And one more reason to plant black-eyed Susans…

Black-eyed Susans are host plants

Black-eyed susans are the host plants to a few butterflies, including the bordered patch, gorgone checkerspot, and the silvery checkerspot.

What is a host plant?

A host plant is an insect’s nursery plant. It’s where butterflies and moths lay eggs and what the caterpillars eat as they grow.

All black-eyed Susans are native to North America

The tricky part? “Black-eyed susan” is a name shared by several different flowers. Latin names cut through the confusion. The ones you want are in the Rudbeckia genus.

Rudbeckia = black-eyed Susan = native plant

A quick Latin name-check helps you plant with confidence, knowing it’s ideally suited for our North American landscapes.

Plant nerd interlude

Where does the name Rudbeckia come from?

According to Texas Park & Wildlife, “Caroleus Linnaeus, the ‘father of modern botany,’ named the flower’s genus for his esteemed professor, Swedish botanist Olaf Rudbeck.” Rudbeck never set foot in North America.

Sigh. More North American native plants named after notable North Americans—ideally, Native Americans!—please.

Meet North America’s black-eyed Susans

Again, it’s going to get a little confusing since they can all be called “black-eyed Susan,” which is why their botanical Latin names will help!

Black-Eyed Susan

Rudbeckia hirta

This black-eyed susan is a knockout for gardens, known for its bright yellow petals and dark brown central cone. It is a short-lived perennial (1-2 years) but will easily reseed itself.

R. Hirta is easily identified by the short hairs on its stems and leaves. It ranges in height from 1 to 3′ and has bigger (but a little more sparse) flowers than R. fulgida.

Black-Eyed Susan or Orange Coneflower

Rudbeckia fulgida

Similar to R. hirta, this species features bright orange-yellow flowers with a dark center. This plant is more dependably a perennial—meaning it will return year after year. R. fulgida has smaller but more numerous flowers than R. hirta. It has hairs on its stem and leaves too, but they are tiny compared to R. hirta.

Although it is sometimes called ‘Orange Coneflower,’ most coneflowers are in the Echnicaea genus. Our Beginner’s Guide to Coneflowers is perfect for more info.

Black-Eyed Susan, Cutleaf Coneflower, or Green-headed Coneflower

Rudbeckia laciniata

Although it goes by a few names, this plant is easily recognizable by its deeply lobed leaves, green cone centers, and because they are TALL—reaching heights of up to 9 feet. Commonly found in moist meadows and along stream banks.

And there’s more…

These are just a few Rudbeckia options. The genus has around 25 species, each native to North America. Here’s a larger list if you’d like to explore more:

Explore other Rudbeckia species

Here are some other species of Rudbeckia native to North America:

| Common Name | Latin Name | About |

|---|---|---|

| Black-eyed Susan | Rudbeckia hirta | Rough leaves with tiny hairs; single yellow daisy blooms; prolific reseeder |

| Orange coneflower | Rudbeckia fulgida | Clumping perennial; orange-yellow daisies; ‘Goldsturm’ is the classic |

| Cutleaf coneflower | Rudbeckia laciniata | Tall; greenish cone; drooping golden rays; deeply cut leaves |

| Rough coneflower | Rudbeckia grandiflora | Rhizomatous; spreads into colonies; tall stems; bold blooms |

| Great coneflower | Rudbeckia maxima | Huge bluish leaves; very tall stalks; drooping rays  |

| Western coneflower | Rudbeckia occidentalis | Dark cone heads; typically no ray petals (rayless look)  |

| Brown-eyed Susan | Rudbeckia triloba | Many small blooms; short-lived perennial; three-lobed leaves |

| Missouri orange coneflower  | Rudbeckia missouriensis | Prairie native; orange blooms; tidy mid-height clumps |

| Sweet coneflower | Rudbeckia subtomentosa | Late-season blooms; ‘Henry Eilers’ cultivar has quilled rays |

| Clasping coneflower | Rudbeckia amplexicaulis | Drooping petals; leaves clasp the stem; plains native |

As you explore black-eyed Susans, you will encounter some plant options with cheeky names in ‘single quotes,’ like ‘Indian Summer’ or ‘Goldsturm.’

These are black-eyed Susan cultivars.

Black-eyed Susan cultivars

A cultivar is a plant curated by humans to look or behave a certain way (here’s our quick cultivar overview.) There are dozens of black-eyed Susan cultivars available, including:

- R. hirta ‘Indian Summer’ This cultivar is renowned for its large, golden-yellow flowers that can reach up to 9 inches in diameter. It is a robust and vigorous plant, often used in borders and as cut flowers due to its striking appearance and long blooming period.

- R. hirta ‘Toto’ This short cultivar is perfect for small gardens and containers. ‘Toto’ has a compact shape and piles of bright yellow flowers with dark centers. It is known for its neat, tidy appearance and long-lasting blooms.

- R. fulgida ‘Goldsturm’ The ‘Goldsturm’ cultivar is a version of Rudbeckia fulgida, bred for an abundance of flowers and heat tolerance. This combination has made it a gardening staple.

- R. fulgida var. sullivantii ‘Viette’s Little Suzy’ A mouthful of a name for a short cultivar! Topping out at 12-14″ high, great for borders.

Every year, new black-eyed Susan cultivars appear, each with different heights, flowering times, and colors.

Botanists and native plant fans have a complicated opinion when it comes to cultivars. Some believe that cultivars are not wise choices, since the genetics have been selected (or sometimes manipulated), which might cause issues if they cross-pollinate with wild species. The Plant Native‘s opinion (if you care—and no worries if you don’t!) is to try our best to plant straight species whenever possible. That said, if you fall in love with a black-eyed Susan cultivar, it’s always better than a non-native plant.

How can I know if it’s a black-eyed Susan cultivar or a straight species?

All cultivars will have that marketing name in ’single quotes’ on the plant tag. If you see just the Latin botanical name—without a cheeky name—it’s probably the straight species. To be extra sure, visit a native plant nursery!

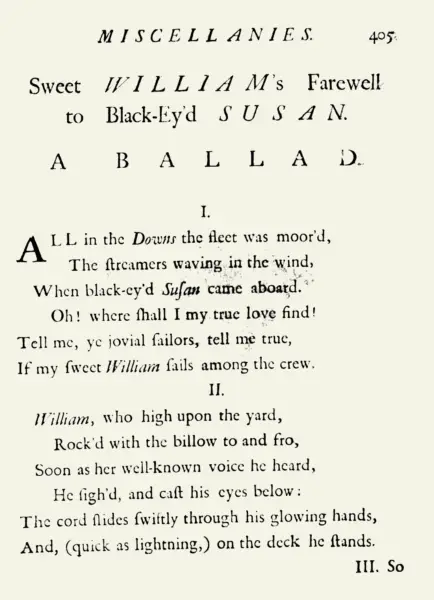

Why is it called black-eyed susan?

According to Texas Park & Wildlife, “the flower’s name likely comes from a popular ballad penned by English poet John Gay (1685-1732). Black-Eyed Susan told the sad story of a crying, lovelorn woman who boards a ship to bid her sailor farewell.”

Womp womp. Here’s the song sung by Patricia Hammond, if you’d like to hear it.

Such a bummer that a weepy European dude named such a stellar, bright, resilient plant. It’s a true disservice to a plant that does not have a black center (it’s dark brown) and thrives in some tough-as-nails situations. Maybe we can change the name to Resilient Susan?

For more plant name fails, read our Terrible Names for Beautiful Native Plants.

Black-eyed Susan is deer-proof

Deer do NOT eat black-eyed Susans. If you’re worried about deer nibbling your garden, planting black-eyed Susans is a good native gardening choice.

How to grow black-eyed Susans

Black-eyed Susans are an incredibly easy plant to grow. They like lots of different sun situations—from full, blazing sun to part-sun. They are also happy in a range of water situations, from extremely dry to occasionally wet.

Grow black-eyed Susans from seed

Growing these natives from seed is easy if you’re patient: plants started from seed will not flower until the next year. This is because in the first year, the plant puts all its energy into growing its root system, which is also what makes the plant drought-tolerant. To grow from seed, you can either start in small pots in early spring and then replant in the garden, or you can directly sow the seeds.

If you get seeds from a friend's garden...

Black-eyed Susan seeds taken from another garden will need to be cold for ~1-3 months before they will grow. The need to be cold before growing is called stratification. Stratification is a part of many seeds that grow in places that experience frosts. A seed knows to stay dormant after it’s cold for a period of time before it sprouts.

You can trick seeds into breaking their dormancy by using a refrigerator or by putting them in a cold, dry place (like a basement or garage). Simply place seeds in a water-tight container and put them in this cold storage for 1-3 months. Take them out and they’ll be ready for growing.

Don’t worry about seeds you buy from a nursery or mail-order: these seeds have already been refrigerated and are ready to go.

How to start seeds in the spring

Black-Eyed Susan seeds can be started indoors in the spring and then planted out in the garden in the late spring/early summer. This is a cheap way to grow lots of plants; a $5 packet of seeds (or a single seedhead from someone’s garden) can grow dozens of plants.

There are lots of ways to start seeds inside, whether using plastic trays and heating mats or simply using washed-out yogurt containers on windowsills. (Native plants literally plant themselves in nature—they don’t need fancy equipment!)

- Pick an airy soil mixture to help the seeds find light and air

- Plant each Black-Eyed Susan seed 1/4″ beneath the soil

- Keep the soil moist but not too wet; a spray bottle can help at the beginning

- Sprouts will emerge after a week of planting

- Transplant when there are at least two rows of leaves on the plant and the nighttime temperatures average 60 degrees.

How to grow from seed in the fall

Growing Black-Eyed Susans by seed in the fall is an easy planting trick. Seeds planted in the fall will not sprout and grow until the spring, but planting in the fall will ensure the plants sprout and grow naturally based on the soil and air temperatures. You can literally sprinkle the seeds in the fall and forget about it until spring, then enjoy plants in the summer.

- Clear an area of leaves, mulch, or rocks using a rake

- Get a packet of seeds or a seedhead from another’s garden

- Sprinkle the seeds on top of the cleared ground; it’s ok to sprinkle quite a few—some seeds will be eaten by birds

- Lightly cover the seeds with soil

- Wait until the spring!

Grow black-eyed Susans from plants

There are four tried-and-true ways to find (or buy) black-eyed Susan plants for your garden:

Where can I find seeds and plants?

Finding native plants can be challenging (we partly blame Marie Antoinette.) To make it easier, we’ve assembled four sourcing ideas.

300+ native nurseries make finding one a breeze

Explore 100+ native-friendly eCommerce sites

Every state and province has a native plant society; find yours

Online Communities

Local Facebook groups are a great plant source

What pairs well with black-eyed Susans?

Black-eyed Susans have lots of plant friends that thrive in similar light/water and look amazing alongside them. A great way to pick flowers is to ensure you’ve got blooms throughout the season, from spring to fall. Here are some options:

Pairs well with

To sum it all up, black-eyed Susans are a must-have addition to any garden. With their bright, sunny blooms, super-easy care, and benefits to wildlife, it’s no wonder that these native North American plants are garden icons. Now you can visit a native plant nursery with confidence, knowing a few differences between the different types (and have a cheat-sheet for the Latin names.) If you’d like to grow a garden filled with bad copywriting, may we suggest Beautiful Native Plants with Terrible Names to find more inspiration? Or meet some other native celebrities in our Beginner’s Guide to Native Coneflowers or our Beginner’s Guide to Native Magnolias. Happy planting!

Sources

- Lang, Kristine. “Rudbeckia: Brighten the Garden from Summer through Fall.” South Dakota State University Extension. September 03, 2021.

- Misc authors. Gardening for Butterflies: How You Can Attract and Protect Beautiful, Beneficial Insects. Xerces Society, Timber Press (2016), 106.

- Paddock, George E. “Lophophora Williamsii: Its Habitats, Characteristics and Uses.” Bulletin of the Lloyd Library of Botany, Pharmacy and Materia Medica 11, no. 3 (1909), 405.

- Royle, Stanley. Honeysuckle and Sweet Peas. Oil on canvas. Yale Center for British Art.

- Yonge, Charlotte Mary. Sweet William. London: National Society’s Depository, 1882. https://archive.org/details/SweetWilliam55271/page/n1/mode/2up.

- Blue Water Baltimore. “How to Choose a Black-Eyed Susan.” Blue Water Baltimore. Accessed July 21, 2024.

- National Garden Bureau. “Year of the Rudbeckia,” September 19, 2025.

- Unknown artist. Portrait of Olof Rudbeck the Elder. Wikimedia Commons.

- Wikipedia. “Rudbeckia.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Last modified July 8, 2023.

- Wildflower.org, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – the University of Texas at Austin, Rudbeckia hirta, 2023.

- Wildflower.org, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – the University of Texas at Austin, Rudbeckia fulgida, 2023.

- Wildflower.org, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – the University of Texas at Austin, Rudbeckia laciniata, 2023.

What if your feed was actually good for your mental health?

Give your algorithm a breath of fresh air and follow us.