Why are Pawpaw trees not everywhere? These trees make North America’s largest edible fruit! The fruit has the consistency and shape of a mango and tastes like a pineapple crossed with a banana. They are also stunning year-round. In the spring, Pawpaws flower with dramatic dark blossoms that look like Tim Burton movie props. In the fall, what was once flowers turns into edible fruit as the leaves turn bright yellow. You’ll need to plant two for fruit—scroll on more planting tips.

Let’s start our love letter to Pawpaws with a basic question:

What are benefits of planting a Pawpaw tree?

The Pawpaw tree has grown in North America for thousands of years. Any plant or tree that has existed in an area for this long is considered a native plant. Every storm, drought, flood, blizzard, and normal sunny day in their region they have lived through. Native plants are made to thrive in their home areas.

Planting native plants and trees—like the Pawpaw—is important for many reasons, including:

- Native plants give butterflies, pollinators, and birds the food and homes they need to survive. The Pawpaw tree is the host plant for the stunning Zebra Swallowtail butterfly (more on this, below)

- Native plants are made to thrive in their home areas; once they are established, they thrive with normal rainfall

- Native plants are gorgeous. As you’ll see in the following images, Pawpaws look beautiful throughout the seasons.

And one more amazing benefit…🦋

Pawpaw trees are the host plant for the Zebra Swallowtail butterfly

Zebra Swallowtail butterflies only lay their eggs on Pawpaw trees. As seen above, you absolutely want to be a part of keeping this magnificent creature alive. This dedicated butterfly-and-plant relationship makes the Pawpaw the host plant for Zebra Swallowtails.

Said simply, without Pawpaw trees, there will be no Zebra Swallowtail Butterflies. (If you are feeling like The Very Hungry Caterpillar got us all off on the wrong foot since kindergarten, thinking caterpillars ate all leaves…well, we agree with you. Here’s a short overview on host plants.)

Zebra Swallowtails need Pawpaws to make a comeback

While Zebra Swallowtails aren’t endangered like Monarch butterflies, they’ve become increasingly rare in many areas where they were once common.

Recent sightings in Pittsburgh, after 87 years, show their return is possible—thanks in part to homeowners planting pawpaw trees. One homeowner even documented growing Pawpaws and raising Zebra Swallowtails on Instagram, proudly becoming a “Butterfly Daddy” to the species. What we plant matters!

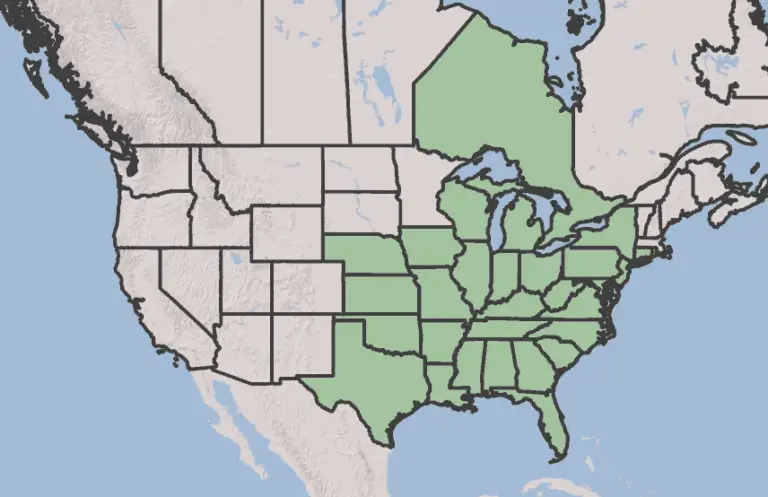

Where are Pawpaw trees native?

The Pawpaw is native to a huge swath of the United States, including the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, Midwest, and the South.

Pawpaw trees through the seasons

As the seasons change, the Pawpaw tree transforms like a chameleon. Here is a quick overview on what to expect, starting in the spring:

Pawpaw trees in the spring

Pawpaw trees’ flowers are unlike anything else in the garden. Their dark crimson blooms look like Gothic sculptures.

Pawpaw trees in the summer

In the summer, Pawpaw trees’ green canopy provides shade as the flowers drop and fruits grow.

Summer is for zebra swallowtails

Once the leaves appear, it’s time for zebra swallowtail caterpillars. Watch for them snacking and building their cocoons in the summer and early fall.

Pawpaw trees in the fall

In the fall, the fruits ripen, and the leaves turn a buttery yellow. Fruit peaks in September and October. As winter begins, the leaves fall, and the tree takes a nap until it’s time to put out its crimson blooms again in the spring.

Now that we’ve gotten to know the plant and said the word ‘Pawpaw’ two dozen times, you’re probably wondering:

Where did the name Pawpaw come from?

The name “Pawpaw” has its origins in the indigenous Taíno language, dating back thousands of years. According to botanist José Hormaza, the name comes from a fateful combination of the Taíno language with Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto’s 16th-century expedition:

“Apparently, the name pawpaw was given to the tree by members of the de Soto expedition for its resemblance to the fruits of the tropical fruit papaya that they already knew, papaya being a Spanish word derived from the Taíno word papaina.” (Source)

(And yes—we’re talking about that Hernando de Soto, which you may remember from elementary school Social Studies. De Soto explored North America from 1539 to 1543.)

To recap:

- The Taíno were a historic indigenous people of the Caribbean.

- Their word for papaya fruit was papaina.

- Spanish colonists applied this word to another fruit they found hundreds of miles away in North America.

- Centuries of usage changed papaina to pawpaw.

What an American name—something that combines indigenous language with colonialism, alongside a game of telephone over the centuries.

Other words we use to trace back to the Taíno people. According to the Smithsonian, “If you have ever paddled a canoe, napped in a hammock, savored a barbecue, smoked tobacco, or tracked a hurricane across Cuba, you have paid tribute to the Taíno, the Native people who invented those words long before Christopher Columbus arrived in the New World in 1492.” The entire Smithsonian article on Taíno history is well worth reading.

Here are other FAQs, before we get into planting and sourcing tips:

FAQs

What does Pawpaw fruit taste like?

At first glance, you would imagine it tasted like mango because of its shape and coloring. Although the fleshy fruit texture is mango-like, the flavor is more of a cross between a banana and a pineapple. You cannot believe that something so tropical-tasting can come from places in North America that routinely experience blizzards.

Pawpaw fruit has been eaten for thousands of years

The history of the Pawpaw is fascinating. Pawpaw seeds and other remnants have been found at archaeological sites of the earliest Native Americans. While the fruit and tree may be lesser known today, this plant has been crucial to North American survival.

Where are good places to plant Pawpaw trees?

The Pawpaw prefers moist, well-drained soil and partial shade (stay away from full, blasting sun). This is because Pawpaws are understory trees, which are smaller trees that grow beneath larger native behemoth trees like Tulip Poplars. Think of them like petite trees that snuggle up next to their taller tree siblings in the forest for protection; they need a little shade.

If you want fruit (and who doesn’t?), you’ll need to plant two

Pawpaw trees need cross-pollination to bear fruit, which means you’ll need to plant at least two trees.

How to plant Pawpaw trees

Planting trees is so easy! You can absolutely do it yourself, no landscaper needed. All you need is a shovel, a bag of compost, and the hose. That’s it! Here’s how to plant your Pawpaw:

- Find a healthy Pawpaw sapling from a reputable nursery; our list of native nurseries makes this easy

- Dig a hole twice as wide and deep as the root ball

- Mix some compost into the soil you’ve just removed and put some back into the hole

- Place your tree in the hole, adding soil until the stem starts at ground level (you may need to remove the tree and add more dirt until it’s right)

- Backfill the hole, gently firming the soil around the roots with your feet

- Add a layer of mulch to retain moisture; arrange the mulch so it makes a little bowl around the tree’s stem (make sure the mulch does NOT touch the stem; this can rot the tree stem)

- Time to water! Give it a deep soak; the goal is to soak the roots

- Keep an eye on your tree, watering it regularly during its first year, and be patient as it establishes itself

Where can I find a Pawpaw tree?

Finding native trees and plants can be a little challenging. Conventional nurseries (and especially big-box stores) typically only carry a few coneflowers or heuchera when it comes to native plants.

Look elsewhere to find a Pawpaw! Here are four tried-and-true sources for finding Pawpaws to plant (and remember—plant at least two for fruit.)

Where can I find seeds and plants?

Finding native plants can be challenging (we partly blame Marie Antoinette.) To make it easier, we’ve assembled four sourcing ideas.

300+ native nurseries make finding one a breeze

Explore 100+ native-friendly eCommerce sites

Every state and province has a native plant society; find yours

Online Communities

Local Facebook groups are a great plant source

What are good Pawpaw pairings?

There are so many native plants that look gorgeous and pair nicely with Pawpaw trees. Some favorites include:

Congratulations! You’re ready to get planting a few native Pawpaw trees. With its ever-changing beauty, delicious fruit, and Zebra Swallowtail nursery abilities, this tree helps turn your garden into a fruit-filled oasis. Gardening doesn’t have to be overwhelming. Planting native is much less work than lawns or non-native gardening. May Pawpaw trees become cherished and tasty additions to your outdoor space. Head over to our plant profile on Highbush Blueberries or Hackberries if you’re looking to plant a fruit-salad-worthy native garden. Or, help the butterflies and plant more host plants. Happy planting!

Sources

- Brown, First-Person Essay by Daniel D., PhD, and First-Person Essay by Daniel D. Brown PhD. “When Zebras Fly: How My Backyard Flora Project Helped Bring a Long-gone Species Back to Pittsburgh.” PublicSource, September 12, 2024. https://www.publicsource.org/zebra-swallowtail-butterfly-pittsburgh-pawpaw-diversity/.

- Hormaza, José I. “The Pawpaw, a Forgotten North American Fruit Tree.” Arnoldia 72, no. 1 (2014): 13–23.

- Johnson, Lorraine and Colla, Sheila. A Northern Gardener’s Guide to Native Plant and Pollinators; Creating Habitat in the Northeast, Great Lakes, and Upper Midwest. (2023), 169.

- Moore, David G. “De Soto Expedition.” NCpedia. Originally published 2006. Revised by SLNC Government and Heritage Library, May 2023. https://www.ncpedia.org/de-soto-expedition.

- Nelson, Gil. Best Native Plants for Southern Gardens: A Handbook for Gardeners, Homeowners, and Professionals, (2010).

- Poole, Robert M. “Who Were the Taíno, the Original Inhabitants of Columbus’ Island Colonies?” Smithsonian Magazine, October 10, 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/who-were-taino-original-inhabitants-columbus-island-73824867/.

- Wharton, Rachel. “The Promise of Pawpaw.” The New York Times, October 19, 2020.

- Winter, Norman. “Paw Paw Trees Lure Zebras and Dark Kites.” Atlantic Journal Constitution, September 12, 2018. https://www.ajc.com/lifestyles/home–garden/paw-paw-trees-lure-zebras-and-dark-kites/qZ2GNa9yrSsqm7fkMauE2L/.

- Wyatt, G. E., Hamrick, J. L., & Trapnell, D. W. (2021). The role of anthropogenic dispersal in shaping the distribution and genetic composition of a widespread North American tree species. Ecology and Evolution, 11(16), 11515-11532. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7944

- Jstor, The Plant of the Month: The Pawpaw.

- National Park Service, The Pawpaw: Small Treet, Big Impact.

- USDA, PawPaw Plant Profile.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Eurytides Marcellus | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service,” August 12, 2009. https://www.fws.gov/species/zebra-swallowtail-eurytides-marcellus.

What if your feed was actually good for your mental health?

Give your algorithm a breath of fresh air and follow us.