Almost every homeowner in the Northeast, Midwest, or Mid-Atlantic wants an evergreen shrub to brighten the winter landscape. Too often, we’ve been stuck with boxwoods—imported, overused, and frankly, a little dull. There’s a better choice waiting in your own backyard: meet inkberry.

Inkberry is a native evergreen shrub that has brightened North American landscapes for thousands of years. Its inky-black berries are what give it the common name—but those berries aren’t for us. Birds and wildlife love them, while humans can enjoy Inkberry for what it really is: a low-maintenance, all-season anchor for the yard. In this article, we’ll explore its name, share planting tips, and suggest some garden pairings.

Let’s start with the obvious question:

Is inkberry a good choice for my yard?

Yes, if…

- You want a native alternative to boxwood that looks good year-round.

- You have a spot with moist soil or a garden that stays damp after rain.

- You’re looking for an evergreen shrub that supports birds with winter berries.

- You don’t mind planting both male and female plants if you want berries.

- You want a low-maintenance shrub that can handle both sun and part shade.

What are other evergreen natives?

There are so many evergreen options that are native to North America. Other options include:

How to grow inkberry

There are a few things to keep in mind if you’re thinking about adding inkberry to your yard:

- Moisture matters. In the wild, inkberry grows in wetlands and along streams. It thrives in consistently moist soil, but once established, it can handle average garden conditions.

- Sunlight. Inkberry does best in full sun to part shade. More sun means denser foliage, while too much shade can make the shrub look leggy.

- Size and shape. Depending on the cultivar, inkberry can range in height from 3 to 8 feet. Use it as a foundation shrub, a hedge, or as the evergreen backbone of a native planting.

- Pruning. Older inkberries sometimes lose lower leaves and look “bare-legged.” Light spring pruning or planting shorter perennials at the base can help keep your garden looking lush.

While inkberry prefers damp spots, mature plants are surprisingly adaptable. If your garden goes through dry spells, a well-established inkberry will usually hold its own.

How does an inkberry compare to a boxwood?

The USDA has a nice description of the differences:

“It provides a larger and faster growing alternative to boxwood hybrids, although it tends to be leggier, prone to stem breakage, and the rhizomatous plants tend to form large, expanding colonies.”

Where is inkberry native?

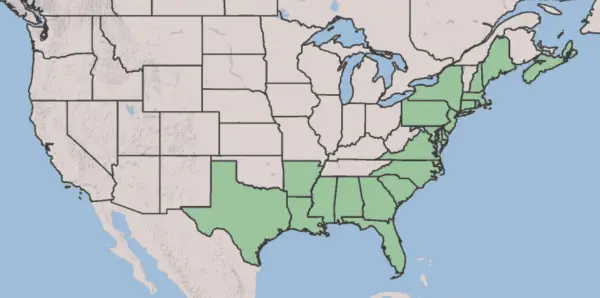

Inkberry is native to half of North America, from Nova Scotia to the Midwest United States.

Why is it called inkberry?

The name comes from the plant’s small black berries, which ripen in late summer and persist into winter. Early Americans even experimented with the berries as a source of dye, though today they’re prized more for feeding hungry birds during the colder months.

Now you’re probably asking—

Can I eat inkberry berries?

No! Inkberry berries are poisonous. Birds can eat them, people can’t.

Want an edible native? Check out our guide to edible native plants, or if you live in the Mid-Atlantic, read our interview about growing a FOOD FOREST!

Nerd tip if you want berries

Inkberry shrubs come in two types—male and female. Only female plants produce the signature black berries, but they need a male nearby for pollination. Bees do the matchmaking, carrying pollen from the male flowers to the female ones. After that, the female shrubs reward you with clusters of glossy black berries that ripen in early fall and last through winter.

Most garden centers sell female Inkberries, so you may need to look a little harder to find a male plant to keep them company. Nursery shopping tip: ask the nursery if they can confirm the sex of the plant you’re buying. If you want berries, you’ll need at least one male in the mix.

Where can I find an inkberry?

We are not going to lie and say that finding inkberries is going to be as simple as driving to your closest plant nursery. It might take a little extra energy to find this native gem, but it is worth it! Here are some recommendations for sourcing this native plant:

Where can I find seeds and plants?

Finding native plants can be challenging (we partly blame Marie Antoinette.) To make it easier, we’ve assembled four sourcing ideas.

300+ native nurseries make finding one a breeze

Explore 100+ native-friendly eCommerce sites

Every state and province has a native plant society; find yours

Online Communities

Local Facebook groups are a great plant source

What are good pairings for inkberry?

Inkberry naturally grows in moist, sunny spots like wetlands and streambanks. It pairs beautifully with other natives that enjoy similar conditions, such as winterberry holly, sweetspire, and red twig dogwood. For a pollinator-friendly layer at its feet, try cardinal flower, blue flag iris, or swamp milkweed.

Pairs well with

And that wraps up our beginner’s guide to inkberry. Forget the plain old boxwoods—this native evergreen brings year-round structure, glossy green leaves, and inky berries that birds love through the winter. Plant it once, and it will anchor your garden for decades. Curious about other native shrubs? Check out our guide to Winterberry Holly or our profile on Mountain Laurel. Happy planting!

Sources

- USDA. “Plant Guide Ilex Glabra (L.) Gray Plant Symbol = ILGL,” n.d.

- North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox, Ncsu.edu. “Ilex Glabra (Appalachian Tea, Gallberry, Inkberry),” 2025.

- Martin, Susan. “Inkberry – a Native Evergreen Shrub – Piedmont Master Gardeners.” Piedmontmastergardeners.org, 2025.

- Schaefer, Louise. “Species Spotlight – Ilex Glabra” Edge Of The Woods Native Plant Nursery, LLC, October 13, 2022.

What if your feed was actually good for your mental health?

Give your algorithm a breath of fresh air and follow us.